For general feedback about the game.

Steam SupportVisit the support site for any issues you may be having with the game or Steam.

On Tuesday we shipped an update that added a bunch of features / bugfixes / balancing tweaks that came out of the community's feedback. In particular, it made some changes to the underlying TF damage system, and as part of that, it modified the way critical hits are determined. We thought it might be interesting to dig a little into the change, and hopefully give you some insight into our thinking.

First, a quick primer on how the critical hit system works. Each player's chance of successfully rolling for a critical hit depends on two factors:

There are two paradigms used for when to roll, and what happens on success:

We had a few things we wanted to change with the old system:

Here are the actual changes we made, taken from the release notes:

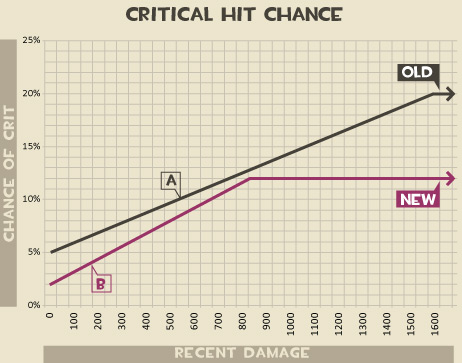

Lets dig a little deeper into these. First, the base critical hit chance was reduced from 5% to 2%. This means that if you haven't done any damage to an enemy, your crit chance is now just under half what it was previously. Secondly, the size of the bonus range was reduced by a third, but the amount of damage needed to earn that bonus was halved. To understand the effect of that, it's useful to graph it:

As you can see, the new crit chance is slightly lower across the board, which we wanted. More importantly though, is that the rate at which the crit chance increases based on the amount of recent damage you've done. We like to think of that recent damage total as a rough measure of your performance.

In thinking about the change we wanted to make to critical hits, we decided that there was a point on the graph of particular interest to us, and that was the point at which your critical hit chance was as much a result of your performance as it was the base chance. If you look at at (A) on the old line, you'll see that point isn't reached until you've done 550 recent damage, a feat that occurs about as often as our backstab code works correctly. That point is reached at (B) on the new line, around the point where you've done 175 recent damage. This means that if you've just singlehandedly killed an enemy Demoman/Soldier/Pyro/Heavy, your next 20 seconds worth of crit chances are already more a result of that kill than the base chance. As a result, if you're a highly skilled player, you're going to fire significantly more critical hits than those around you. And remember, if you've just killed 2 or 3 enemies, now's the time to push!

The Scout was one of the first TF2 classes we worked on when we decided to try out a more stylized approach to the game. As a result, his concept art is further afield, and in the eyes of our artists, much more embarrassing. This might be exacerbated by their desire to not have people looking at a piece of their artwork and not liking it, from an artistic point of view. Concept art has a different purpose than that, and so the effort to make it look great is usually unnecessary. In short, there's a special place in hell that all our artists hope we'll go to for showing you their concept art.

Dhabih threatened us in various ways not to show anyone his Scout concepts, so we told him we wouldn't do that. Luckily, he doesn't read the internet much, preferring to spend his time sipping lattes at locally owned organic vegan coffee shops, so if you don't tell him you've seen this concept art, we won't.

We're just about done with the Scout pack, and our design and coding has already moved on to the next pack. The weapons and achievements are all nailed down, and we just have to finish up the final artwork on them. We like to do the final art as late as possible to ensure that we don't waste any work, which turned out to be a good decision this time around due to the large number of unlockables we tried out as alternatives to the Scattergun. Balancing his replacement weapon has been very tricky due to large threat difference of the Scout between skilled and non-skilled hands. More on that soon.

In the meantime, here's a few answers to some questions we get regularly:

"When's the next update going to be out?"

"Why did you change the minigun's muzzle flash away from the original one shown in Meet the Heavy?"

"Why should I use Natascha? And doesn't she only do 66% damage, not 75%?"

"Why is the Sniper such a fake Australian? Aren't several members of the TF2 team Australian?"

We've been pretty quiet lately, but thankfully, that's about to end. In the next few days we'll have an update out that has a couple of new features for the Engineer and Spy, and a variety of other smaller fixes.

These are just to work on some class balance and depth issues that we've seen in the wild with these two classes, but aren't meant to replace their entire class packs. They will be getting more attention further down the road.

While that's in testing, we're off working on several things that folks have been emailing us about, so we thought it'd be good to provide some detail:

If you wish to watch this video, you will need to Download the Flash plugin.

Since the release of Meet the Sandvich in August, several people have asked us how something we'd boasted would be "our magnum opus," "over four hours long" and "make Citizen Kane look like something dumb a complete idiot would make," ended up being one un-dramatic minute spent inside a refrigerator.

Now that more than a month has passed and the wounds have healed on Meet the Sandvich, we can finally give you an honest account of this aborted 240-minute epic, and by that we mean point fingers: It was all the bean counters' fault.

The suits took issue with every brave, authority-questioning page of our Meet the Sandvich script-specifically that there were supposed "similarities" between it and the 1987 action film Predator, and more specifically that it was word for word the 1987 action film Predator.

"Could you explain to us how your script is in any way different from Predator?" asked one of the suits.

"Predator takes place in Guatemala," Erik Wolpaw explained, using his I'm-explaining-something-idiotic-to-a-child voice. "Meet the Sandvich takes place inside a refrigerator in Guatemala."

"Where you can hear Predator happening outside of the refrigerator," clarified Jay Pinkerton.

"Also, Predator is two hours long," Erik continued. "Ours is four hours long."

"Right," said a suit, "but only because the script includes the first half of Predator..."

We nodded.

"... then all of Road House, and then the rest of Predator."

More nods. For a bean counter, this guy had really done his homework. Much like Dutch, when Dillon explains to Dutch how the Predator uses the jungle to its advantage, these suits really "got" it. We let our defenses down.

"Our script is pretty much exactly like Predator," Jay agreed.

"We took the script for Predator and put our names on it," Erik added, in case this hadn't been clear.

"Also, we had to paste the script for Road House there in the middle," Jay said when it suddenly occurred to him that business types who don't understand the creative art of writing might think merely writing your name on the Predator script isn't a full time job for two people. With everyone apparently now on the same page, Jay began working the room and shaking hands.

As it turns out, we'd been led, like the Predator by Dutch, into a trap. Instead of sharpened bamboo and weighted jungle pulleys, though, this was a trap of words, and instead of the Predator, it was us.

The suits demanded we give them the script so they could shred it. Just like in Predator, Jay doused the script pages in mud to conceal their heat signature from the suits. Unlike in Predator, this did nothing. The script was confiscated and destroyed. This created a small problem for all the Team Fortress actors we had standing around in the recording booth, watching us through the window with increasingly visible agitation.

"Hello?" barked Rick May, the voice of The Soldier. "Are we doing this or not?"

"Oh man, we are going to get fired now," Jay said. "We'll have to get jobs! We'll have to..." Jay tried to think, failed, then gave up in frustration. "What do people who aren't writers do?"

"I think they... sell things," said Erik, clutching at fuzzy images of people he'd walked past on the street on the way to nice restaurants. "Shoes and watches. From behind tables." He remembered his butler, who wasn't a writer. "Oh! Or they serve things."

"What are you two idiots talking about in there?" asked Gary Schwartz, the voice of the Heavy.

Jay grabbed the intercom mic. "Shut up, please," he observed.

"Anyone else notice this script is basically Predator?" Nathan Vetterlein, the voice of the Scout, asked. "It's not just me, right? This is word for word Predator."

"You think you can do any better?" spat Erik, a cloud of sandwich chunks hitting the sneeze guard they put between actors and writers in professional recording studios.

"You think what we do is easy?" screamed Jay, sending a further cascade of sandwich onto the sneeze guard. "Where would you have put the script for Road House into the script for Predator, smart guy? At the beginning? Because then it's just two movies," he said, not even believing how stupid someone could be to do that. He put his sandwich down to better illustrate the point with his hands, using his open palms to signify two different scripts, then bapping them together to further illustrate how stupid that would be.

Just as Jay's sandwich hit the table, a light went on in the refrigerator in Erik's head. "Sandwich... Sandwich! Say..." He punched the intercom. "Hey, guys? This is gonna sound crazy, but I have a new direction I want to try. Who's seen the movie Predator?"

"I have!" Jay exclaimed, thrusting his hand into the air.

Erik began to pace. "We open on a chopper. Inside sits Dutch, muscles bulging thr—"

"Look," Rick May interrupted, "how about we just improvise something?"

"Improvise..." Erik said, stretching the "s" out thoughtfully while staring at the ceiling.

After a minute of Erik saying "sss" followed by a gasping gulp of air followed by a few minutes of silence, Rick May tapped on the glass and asked us if we wanted him to tell us what "improvise" means.

It turns out "improvise" is another word for "the writers just watch," which sounded good to us. Better yet, the improvising was a big success, and led to the dialog you heard in Meet the Sandvich: rude, raw and spontaneous, like freestyle rap (or, as Valve writer/amateur freestyle rap impresario Marc Laidlaw refers to it, the poetry of the streets.) Here's a sampling below of some of the stuff we didn't end up using:

Heavy:

"What's that, Sandvich?"

Scout:

"Gimme back my legbone!"

"He's like a big shaved bear!"

"Pain!"

"I regret everything!"

Soldier:

"We got him by the short and friskies!"

"Don't do it!"

"You're writing checks your butt will find uncashable!"

"You only get one!"

"You call that killing me?"

"I will pay you all of my money!"

"Half the blood in your body!"

After an hour of high quality stuff like the dialog above, the writers had gained enough confidence to improvise some of our own. Here's a line we improvised ourselves from the movie Predator:

"I don't have time to bleed!"

Another improvisational gem, courtesy of Valve's award-winning writing staff, unilaterally tag-team writing alongside the powerhouse writers of Road House:

"Pain doesn't hurt!"

Here's a line we improvised that almost did make it into Meet the Sandvich, and was only removed after a non-writer dropped by our office and pointed out that we hadn't actually written it per se, and in fact had stolen it outright from The Simpsons:

"He's already dead!"

The point for all you young writers is just this: if the constraints of your current project don't specifically forbid it, your best writing will always result from writing your name on the Predator script. If, for whatever stupid reason, this isn't an option, improvise. Improvised dialog feels more real because it's lived. More importantly, it requires no actual writing.